Today I am providing my English translation of an article by Maria Morigi, originally in Italian, published on ComeDonChisciotte.org on Wednesday 18th June 2025. (All formatting and footnotes original).

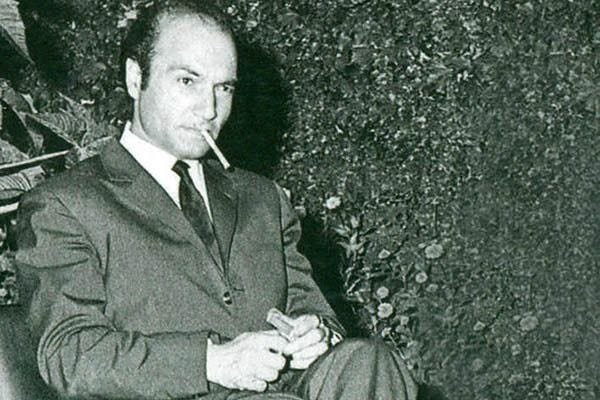

1While Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini played a fundamental political and charismatic role in the 1979 Revolution, the real “ideological driving force” behind the proclamation of the Islamic Republic was 'Ali Shari'ati Mazinani (1933–1977), a figure known in the West only to those interested in political Islam. A sociologist, philosopher and scholar of Marxism, one of the most influential Iranian intellectuals of the 20th century, Shari'ati was imprisoned from 1973 to 1975, then exiled to London, where he died of a heart attack in Southampton at the age of 43. It can be said that Shari'ati is to the Iranian Revolution as Marx is to the Russian Revolution. Yet neither of them saw the revolutionary fruits of their ideology.

Shari'ati's father was a teacher who founded the “Centre for the Propagation of Islamic Truths” in Mashhad in 1947 and was active in the National Front, a coalition of social democratic, constitutional monarchist and Islamist groups with a popular nationalist social agenda. Already in Mashhad, the young Shari'ati was familiar with the ideas of thinkers such as Jamal al-Din al-Afghānī, one of the founding fathers of reformism, the “Islamic Awakening” (Nahda), and Muhammad Iqbal, poet and philosopher founder of independent Pakistan, but he was also familiar with the works of Sigmund Freud and Alexis Carrel, French surgeon, physiologist and biologist, winner of the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1912.

In 1958, Shari'ati entered the University of Mashad; after completing his Master's degree in 1960, he won a scholarship to the Sorbonne for a PhD in sociology and Islamic history and, in Paris, he immersed himself in radical political philosophy by participating in revolutionary organisations such as the Iranian Student Confederation and the Iranian Liberation Movement, formed in 1961-1962 by followers of Mohammad Mossadeq. He became interested in Third World-ism with the idea that class struggle and revolution would lead to a just society freed from the burden of colonialism. He was influenced by Albert Camus (with the work “The Rebel”), met Jean-Paul Sartre and Franz Fanon (psychiatrist and Third World anthropologist, author of “The Wretched of the Earth”), and saw revolutionary Islam as a fusion of traditional and international, left-wing and religious elements, a possible way to guide the Iranian intelligentsia.

Shari'ati's thinking was based on the assumption that Shi'ite Islam was by nature a revolutionary ideology and that religion was a driving force capable of elevating human beings. Insisting on the search for the “Way of Revolt” to redeem the country and establish a classless society, he explored socialism and Marxism, but he was also convinced that Marxism alone could not fully provide the means for the liberation of the Third World from Western imperialism, which could only be fought by the Shiite masses through the recovery of their original Muslim identity.

On this theme of identity, during his years in Paris, Shari'ati translated the text “Abu Zarr. Khodaparast-e Sosiyalist” (“Abu Zarr. The Socialists Who Worship God”) by the Egyptian novelist 'Abd al-Hamid Jawdat al-Sahar, which recounted the life of one of the Prophet's first companions who, after Muhammad's death, denounced the caliphs as corrupt and retired to the desert to lead a simple life among the hungry and the poor. Shari'ati's socialism is tinged with spirituality and mystical fervour, so much so that Abu Zarr can be defined as the first Muslim socialist, a “primordial person” in whom logic has not yet replaced conscience2.

In his essay Red Shi'ism vs. Black Shi'ism, Shari'ati discusses the dualism inherent in the Shi'ite religion. Red Shi'ism, free of idolatry and clergy, is the pure form of religion centred on social justice, redemption and the salvation of the masses. Black Shi'ism, dominated by the Safavid monarchy and the reactionary clergy, is instead the deviant form of religion, far removed from the needs and aspirations of the masses. In his essay Islamology (1969), Shari'ati asserts that Islam is compatible with modernity because it is based on consensus (shūrā) and therefore on democracy. Unlike conservative Shiites, he harshly criticised the ulamā class, guilty of using religion as “the opium of the people” by turning it into dogma. Inconsistent and vague issues such as mysticism and eschatology used by the ulamā prevent people from discovering the depth of religion and also from seeing their own misery. “We must reform Islam, making it the driving force for the liberation of our societies, which are still stuck in a tribal social dimension, that is, in the Middle Ages of the East…”3.

Shari'ati believed in the universal law of determinism, certain that evolution and revolution were inseparable and inexorable, leading to the inevitable end of history with the realisation of a utopia in which equality and unity would reign and the Mahdi would return, the culmination and end of the struggle. According to Shari'ati, the root of all human problems is private property, the advent of the machine, and the dialectic based on conflict and war. The latter is expressed in the myth of Cain and Abel, a metaphor for class struggle, in which Cain represents the rulers who exploit the poor masses symbolised by Abel. Like Marxists and liberation theologians, Shari'ati saw the main cause of evil in the perverted “system” of a corrupt society based on the idolatry of the “Trinity”: politics, economics and religion, a three-faced idol (Pharaoh, Croesus and Balaam) in which the masses, drugged by religion, are forced into submission and exploitation. Thus Shari'ati interprets the language: Ummah is the “society in permanent revolution”, Tawhīd is “social solidarity”, Imām is the “charismatic leader”, Mujāhid is the “revolutionary fighter”, Mustazafin (the “shoeless”) are the “oppressed masses”. The martyrdom of Karbalā became the moral lesson based on the voluntary sacrifice of revolutionaries. Since the Qur'an taught that political, economic and religious power belongs to the people and that society represents God on earth, this means that there should be no monopoly of power by the clergy, and that the Shiite faith rooted in the masses is itself a progressive movement towards the revolutionary goal, demonstrating that man is a creature aimed at the realisation of a classless society, freed from tyranny, injustice and deception.

Shari'ati also gave great prominence to the revolutionary weapon of martyrdom, which motivates men to become witnesses to the true values of Islam. The idea of martyrdom, linked to the history and tradition of Shiism, also spread among the more radical Sunni movements. But it was in these pre-revolutionary years that the idea arose that a martyr is not only someone who fearlessly faces death for the cause of God, but also someone who voluntarily kills himself to cause harm to the enemy. Martyrdom is a choice that guarantees honour, faith and the future of the powerless. It transforms Shiites from passive “guardians of cemeteries” into active followers of the First Imam ʿAlī.

The Iranian Asef Bayat, a witness to and participant in the 1979 revolution, recounts that portraits of Shari'ati were present during the protest marches of the mid-1970s and that his epithet mo'allem-e enqilab (“revolutionary mentor”) was chanted by millions of people. M. Campanini, one of the leading experts on Islamic political thought, argues4 that Ali Shari'ati “can certainly be considered not the first, but certainly one of the most effective theorists of revolutionary Shiism; a Shiism that takes on the fundamental characteristics of an ideology (...) Ali Shari'ati's lectures, conferences and books had a profound impact on the formation of Iran's revolutionary youth…"

The article is taken from Maria Morigi's essay “Islam tra colonizzazioni e imperialismi. Percorsi su Islam e islamismo dal XIX al XXI secolo” [“Islam between colonisation and imperialism. Paths on Islam and Islamism from the 19th to the 21st century”], Ed. Anteo 2025 (Chapter 3, paragraph 3, page 73 ff.).

“Here it is said that Abu Zarr himself claimed to have met and prayed to God three years before encountering Muhammad. When asked in which direction he had turned to pray to God, he replied: “In the direction in which He made me aware of myself”. Quoted from Daniele Perra, “I socialisti che venerano Dio” [“Socialists who worship God”], Arianna editrice, 14/05/2024.

Cit. Esposito, ed. Voices Of Resurgent Islam, New York: Oxford University Press. 1983.

Massimo Campanini, “L’alternativa islamica” [“The Islamic Alternative”], Ed Mondadori, 2012

Article d'une importance Capitale sur la connaissance du Shiisme loin de la propagande que l'Ouest voudrait travestir et utiliser pour l'imposer comme une branche de l'Islam négative plus radicale que le Sunnisme. Faute d'essayer.